The Cop & The Fugitive:

In an era, when cops could be trusted to go after criminals, without the help of computers and mobile phones, Inspector Zende made it to the police and media hall of fame by capturing the serial killer and fraudster Charles Sobhraj.

The world has encountered worse criminals since the time Sobhraj; back then the notorious “bikini killer” with a habit of slithering out of prisons, was so fascinating, that books were written on him, documentaries and feature films made. In the recent web series Black Warrant he (portrayed by Sidhant Gupta) played a starring part.

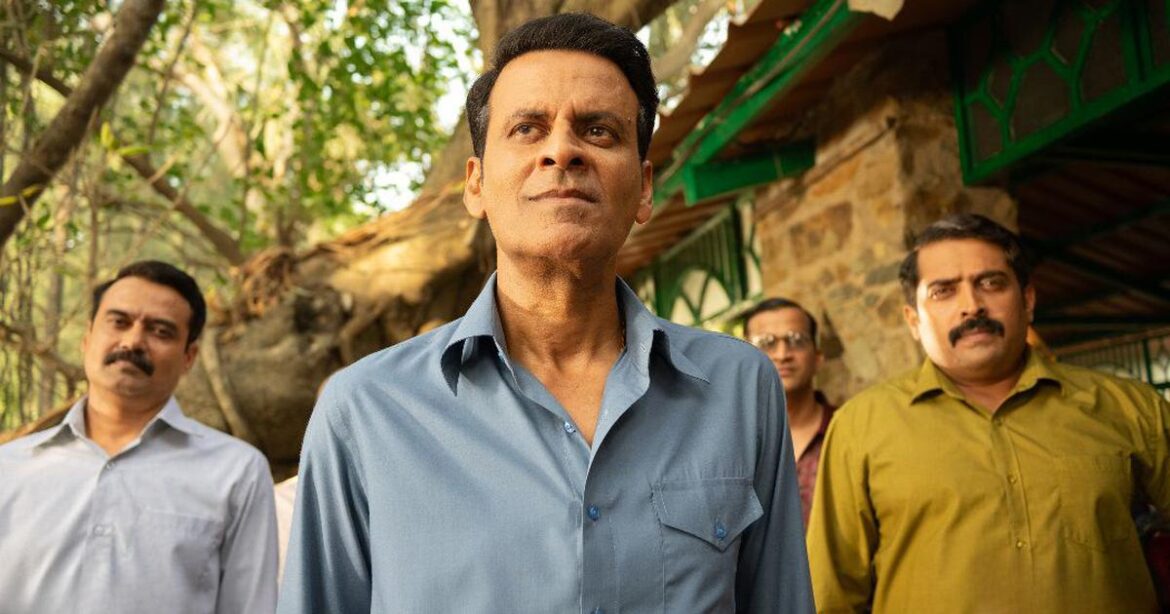

In the Netflix film Inspector Zende, written and directed by Chinmay Mandlekar, the eponymous cop is played by Manoj Bajpai with is usual verve, as he gets jolted out of the chawl home he shares with his wife (Girija Oak) and son, when he hears of Carl Bhojraj (Jim Sarbh), escaping from a Delhi jail. The criminal he arrested seven years ago is on the loose.

Zende is portrayed as ordinary, with a zeal to do his job well, but without the swagger associated with screen supercops. When Bhojraj escapes from Mumbai to Goa under the noses of Mumbai cops, Zende’s boss (Sachin Khedekar) sends him and a team of out-of- shape cops to hunt for the fugitive. The mission is supposed to be secret and Goa police have to be kept at bay. Dressed in a borrowed coat, Zende flies for the first time, with his equally excited team, and starts the search the old-fashioned way, following clues and questioning possible witnesses. Meanwhile a bewigged Bhojraj lives it up in Goa, drugging, robbing and burning his hapless victims.

Zende is not particularly bright, and Bhojraj is luckier in his escapes than especially sharp; Mandlekar treats it as a mild farce, instead of a serious police procedural. Zende is not given any kind of image—past successful handling of cases, for example. When he is introduced, he is lining up at a milk booth with empties. When police work in today’s films and shows is seen as glamorous, risky or both, Zende and his Agripada Police Station could not be more lethargic if they tried. But Sobhraj was caught with a mix of meticulous following of clues and plain good luck. There are bureaucratic hassles, like the one cop tasked with keeping accounts fretting about receipts, and running out of money. In the meantime, the myth of Sobhraj/Bhojraj has consumed the press, police and politicians alike.

The man they are after, just flits through the movie, in his elaborate wig and French accent, so that he does not even feel like a threat to Zende or his men. It is as if the film – unlike an efficient documentary on the cop made by Akshay Shah—wants to show that catching criminals has more clerical nitpicking than shootouts.

(This piece first appeared in seniorstoday.in)