As Mita Vasisht starts a long run of her play, Lal Ded, this week, here’s revisiting a recent interview :

In spite of keeping busy with films, television, web series, and theatre, Mita Vasisht keeps returning to the solo performance, Lal Ded, which is dearest to her heart.

She has performed this play about the Kashmiri mystic-poet for fifteen years, finding in her the core of Kashmiriyat, as conditions in the troubled state fluctuate. She is preparing to do a nine-show run soon, and it has got her spirit churning once again. “Things have changed a little,” she says, “now I have started becoming very interactive with the audience. Like, I get the audience to walk with me through some of the Kashmiri Vakhs (Lad Ded’s poems), to get them the flavour of the language on their tongues, because I make them recite with me… we have a bit of fun with it before the performance starts. It’s almost like a purvaranga (preliminaries) which we used to do in Sanskrit theatre earlier. It’s a bit different because there is no prayer, but you actually settle the audience into the mood of what the play can be.”

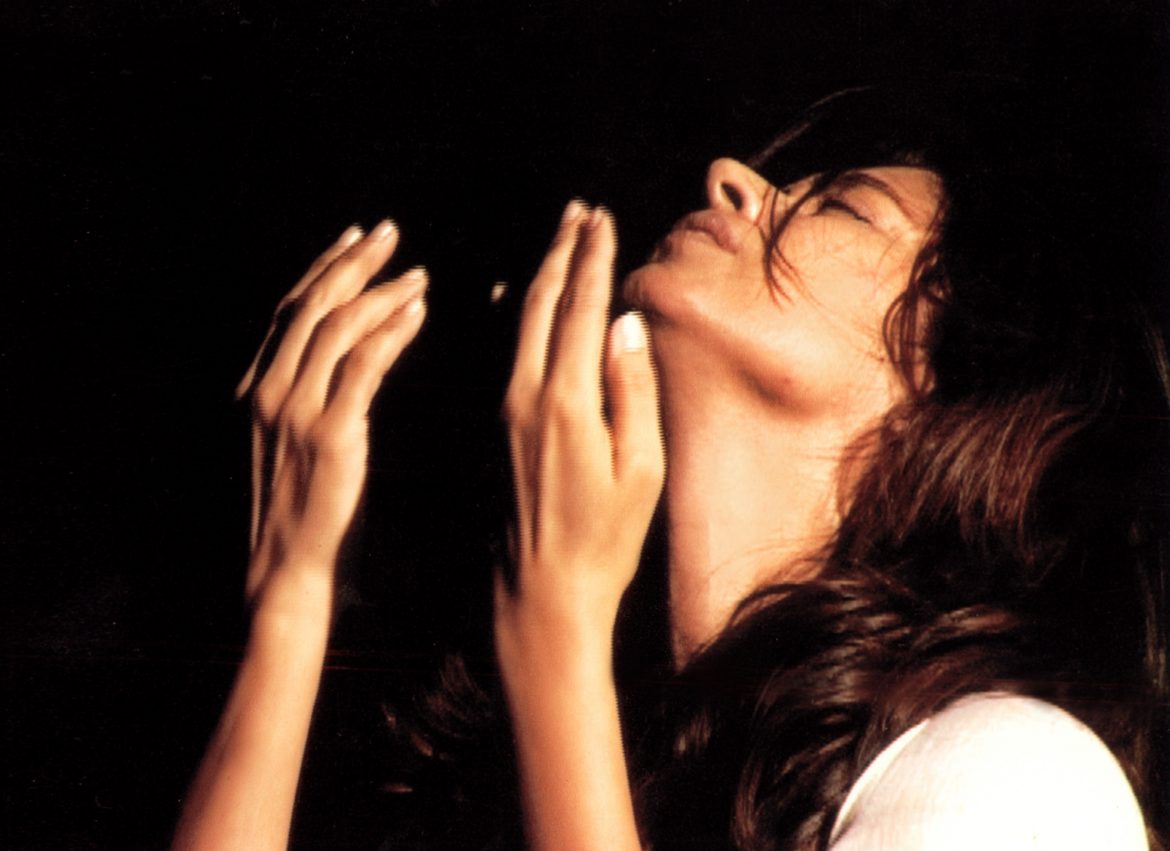

This time, she plays to follow the shows with workshops, in which she will share the process of the play, which took almost three years. “For instance,” she explains, “I would like to know if they spotted the gesture from Leonardo da Vinci’s painting The Annunciation. When I teach acting, I very often deconstruct that painting in class, for the students to understand the mechanics of the body. So it might be interesting for an audience to understand where sculpture came in, where Noh came in, where Kudiyattam came in and why, and to begin to see the processes because every art form takes you through reality in a very different way. That is why I need to deconstruct the craft of my play.

“That the terrain the poet comes from, the geography also informs the music and physical performances, is something I want to get my audience to understand, because I think it has become really important in these times of trying to make everything global. But what you end up doing is flattening out all the ethnicities and cultural nuances. What I am also going to do at the end of the workshops, after people have understood, form structure, scale, aesthetics, geography, and all of that, is to tell them, now find one sentence inside yourself that you would really like to articulate, but you have not done it so far. Then write me a four-line poem. I want to do this in many cities and especially with young people, because I want to see what introspective space they have within them, or do they actually have it at all? Which in itself will be telling. Is there something about them that is their own, and not just informed by so much public opinion and social media around. It might be interesting to pick the best poems and publish them.

“Lad Ded is a very introspective piece,” she continues, “people relate to her, because she cuts through all the isms of religion, form and time, and goes way beyond that. So she is, in a way, the pure self, which every person has inside them, till they are indoctrinated into a religion or sect. There is a certain purity to the performance, so my effort at all times, is to keep that purity, because, it is very easy to stay with the structure and lose the soul. Which is why the construct of the play is a bit dangerous, because you can’t improvise and create these so-called surprise elements. You have to stay in the fixed form, at the same time, each time, you have to elevate yourself to rise above the form, in the spirit. The angik (body) and vachik (voice) are usually at par, but changes have also to be made according to the space. In theatre, you need an image that will stay, that grabs you. Theatre is meant to make images that are out of the ordinary, which jolt you into a sense of what is this and why is it; which make you question the premise of what you are seeing. That is important to me about theatre, and it can’t be arbitrary, it has to be within the construct of whatever the aesthetic is.”

Agnipankh

Mita has acted in plays like August Osage County, Jug Jug Jiyo, Agnipankh and Aarohi, travelling extensively with them. However, she finds that some of the stage directors she has worked with, have a “chalta hai” (make do) attitude to the aesthetics of theatre. “I think there should be excellence in every department. The director says, the story is strong enough, nobody is going to notice if the lights or sets are not so realized; why would you not take care of these aspects of a performance? The Natyashastra talks about aharya (decorative elements) too along with angik and vachik.

“People are not happy of you give them something they have not imagined; it threatens them, their sense of power. Therefore they want to find ways of controlling or diminishing it. I read that Meryl Streep had a really bad time in drama school, because there would be directors who harassed and harangued her– they understood that a lot of what she was doing, they could not take credit for. I find it distressing to deal with issues of ego and power play. Obviously when I am doing my own play I don’t have that, in fact what I love about doing theatre and working with other people when I am the boss, is how much I sublimate my ego. When you are in charge, it is a place of enormous giving and generosity– I personally cannot keep a team together, unless these elements are in place. But many directors like the actor to be subservient and obsequious to them.”

When Mita was selected to study at the National School of Drama, there was a psychology test in which they were asked to visualize which rung of a ladder they see themselves on when they start and where they see themselves three years later. “I put myself on rung two at the beginning, because I was already an MA in Literature, and had done theatre for a year, and after three years I put myself on rung three, because it was just the beginning of the journey. I knew that those three years would be, for me, a space to completely explore what I am capable of. So I attended every class and every workshop, whether it was miniature painting, sculpture, poetry, martial arts, mime, dance – I understood even then, that acting was not just being on stage and saying your lines, it was a way of life. For me the world of acting was a place where every other branch of learning had a space that I could attach myself to, and detach at will. In order to do that, I had to access every aspect of the performer’s art. Between 1984 and 87, we had the most marvelous minds as teachers, who were legends in their fields. Nibha Joshi, who taught aesthetics, told me in the first year, ‘You have a very fine brain and intellect, but you have to learn to be stupid. You have to bring your other senses into play and not just use the mind.’ It took me three years to reach that stage, when all the research was inside—I could wrote a thesis on every role I did– but the performance was free of that; it was just about the body.”

Mita believes she would do a lot more theatre, if she were financially stable. “I am also blessed because along with plays, I do films and TV — I am equally proficient in all three. But I love doing theatre, because it allows me to be more complete as a performer than films these days do. It is also much more challenging in a lovely way. It makes me a more rooted person, I feel like there is a reason why I am in this world.”

(This piece first appeared in The Hindu Friday Review dated December 5, 2019)