The Woman Who Would Not Weep:

On Dimple Kapadia’s 65th birthday, revisiting her National Award-winning film Rudaali.

The woman is called Sookhi Shanichari (Dry Shanichari), because of her notorious inability to weep. She suffers pain, indignity and abandonment with a stoic fatalism not common in the rural milieu where she belongs.

In fact, weeping is actually a profession—rich people hire mourners or rudaalis because their dramatic staged display of grief boosts the status of the dead person, who might actually go unmourned, especially if he were a hated patriarch. Dressed in black, hair left loose, the rudaali beat her breast, rolled on the ground in simulated agony, and shed artificially induced tears to lament the death of the ‘client’ so to speak.

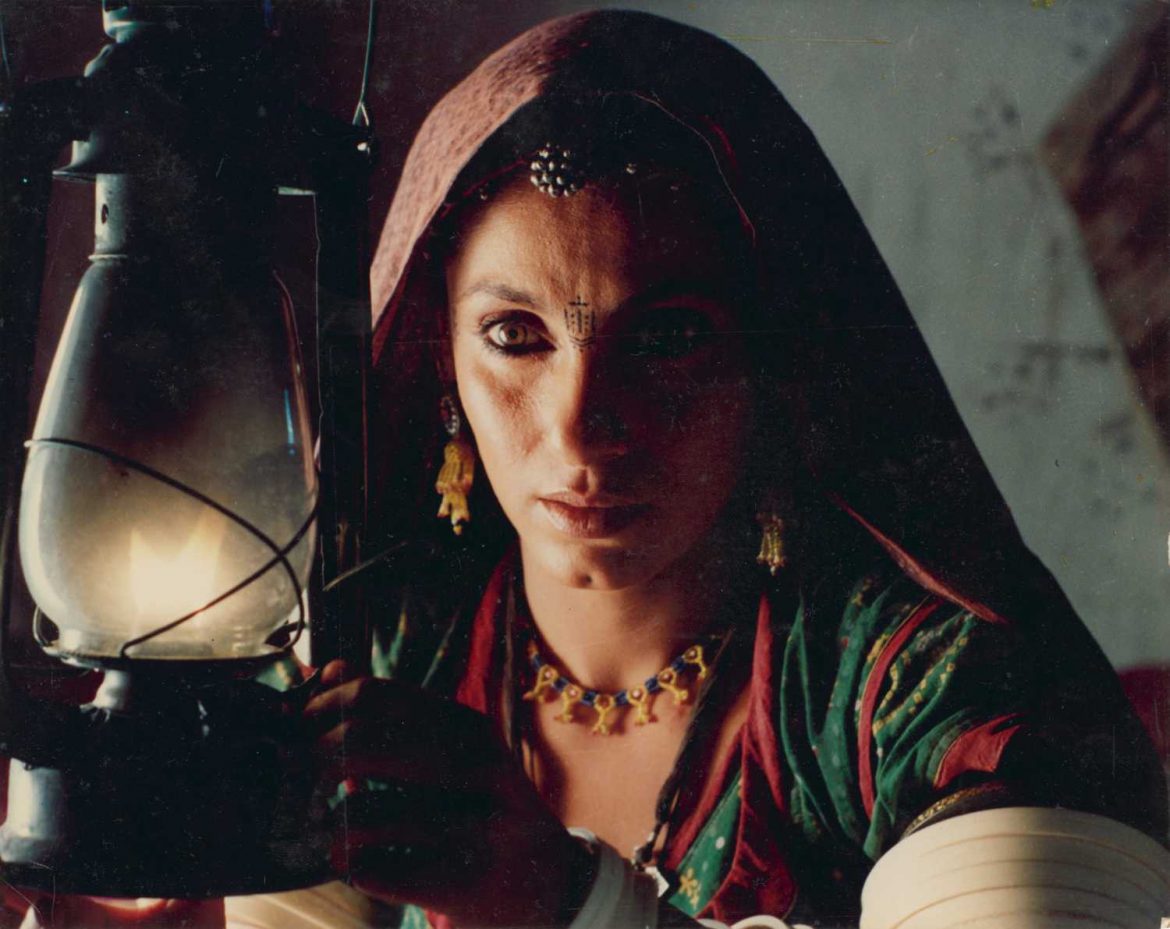

Dimple Kapadia, going against her glamorous image played a Rajasthani village woman in Kalpana Lajmi’s Rudaali (1993) and won a National Award for it.

Till this film, Dimple Kapadia was admired for her beauty, her debut in Raj Kapoor’s Bobby, throwing up of a promising career for a sudden wedding with superstar Rajesh Khanna, the dramatic break-up after two children, the comeback with Sagar. Then, with surprising indifference towards a career she fought to regain, she made a haphazard choice of roles that included an enigmatic ghost in Gulzar’s Lekin and the B-grade, faux feminist shocker Zakhmee Aurat, in which she and her gang of angry women went about castrating rapists.

Rudaali matched her legendary beauty with her underutilised talent, and with remarkable lack of vanity she played an embittered Shanichari, dressed in drab, shapeless outfits, looking much older that her age, her face bearing the mark of suffering and lost hope.

The film was based on a short story by great Bengali writer Mahasweta Devi, whose stories focussed on underprivileged women. Lajmi shifted the location to a more vivid landscape of Rajasthan, where the sandscapes, bright costumes, palaces and feudal structure made for a more visually arresting backdrop.

Here a chatty Bhikni (Raakhi) comes to stay in Shanichari’s humble hut, awaiting the death of the zamindar (Amjad Khan), so that she gets a mourning job. Shanichari finds in Bhikni the friend and confidante she never had. Shanichari is so reviled by the villagers for being unlucky that she chants their curses as her introduction–the woman born on a Saturday, whose ill-fated birth killed her father, and drove away her mother.

Shanichari lost her mother-in-law and her husband to illness, and later was abandoned by her son Budhua (Raghuvir Yadav). Budhua, who has a tendency to disappear for days, married a prostitute, Mungri (Sushmita Mukherjee), who aborted her baby in a rage, leaving Shanichari bereft of her only chance to have a grandchild.

When she talks to Bhikni, the one happy interlude in her life emerges— the attraction of the landlord’s son Lakshman Singh (Raj Babbar) towards her. He hires her to look after his pampered wife and does not treat her like a low-caste serf, telling her often to look up at him when he addresses her. He invites her to sing at his son’s birthday and gifts her the land her hut stands on.

Shanichari’s eloquent eyes speak of admiration for Lakshman Singh; it is clear he loves her in a way, but is not the kind to force her into an illicit affair. After the night she sings for the family (the memorable Bhupen Hazarika composition Dil hoom hoom kare), she never meets Lakshman Singh again, making a living doing hard labour at a stone quarry and later selling quilts in the bazaar.

Through all her troubles, Shanichari remains dry-eyed, but anger simmers in her heart—at the fate of poor women like herself. Her low position in the rural hierarchy gives her the courage to publicly castigate the village priest and shopkeeper when they hit on Mungri and abuse her.

Shanichari has the resilience of many rural women, who are not even aware of their own strength. Once they have no man or family to depend on they attain a kind of fearlessness that helps them get through their tough life. It was Kalpana Lajmi’s direction or some inner reserves of pain that Dimple Kapadia brought into her very bearing, that imprint Shanichari on the viewers’ mind.

One night, a man comes to fetch Bhikni. Someone she knew in the past is dying in another village and sent for her. She promises to return in two days and then tell Shanichari her story. The man was actually her lover, for whom she had abandoned her family and joined his nautanki company. When cinema arrived and killed folk theatre, Bhikni was forced to become a rudaali.

The zamindar is on the brink of death now and Shanichari goes to meet Lakshman Singh who is planning to leave the village. The brief encounter shows that he still has feelings for her. There she hears that Bhikni is dead, and also learns that she was her mother.

Bhikni’s death unleashes Shanichari’s tears in an uncontrollable torrent of grief. Her mother left her with a legacy too— the ability to weep, that turns Shanichari into a rudaali.

There is a lot that is left unsaid in the story and in Lajmi’s film—about the condition of women in feudal society. Still, women like Bhikni and Shanichari find ways to survive without losing out on their self-respect or dignity. Bhikni does it by breaking the rules, Shanichari by reluctantly obeying them.

Dimple Kapadia’s divergence from typical Bollywood gave her opportunities for other offbeat roles in films like Mrinal Sen’s Antareen, Govind Nihalani’s Drishti, Somnath Sen’s Leela, Farhan Akhtar’s Dil Chahta Hai, Homi Adajania’s Being Cyrus and Finding Fanny and more recently, made her international debut in Chritopher Nolan’s Tenet, but it was Rudaali that had unlocked her potential.

(This is an edited version of a chapter from my book Sheroes: 25 Daring Women of Bollywood, published by Westland in 2015)