The names Mary Ann Nichols, Annie Chapman, Elizabeth Stride, Catherine Eddowes,Mary Jane Kelly do not ring any bells. But everybody has heard of Jack The Ripper, a notorious serial killer who has been mythologized by books and films, mainly because he was never caught. At least five of the gruesome killings in Whitechapel, the poor part of London in 1888, were attributed to him, because of a similar modus operandi—slitting the women’s throats and dismembering them. The media of the time, as ghoulish and sensation-seeking as always, dismissed the women as prostitutes, which automatically meant the police could tone down the hunt for the killer, who, for months, terrorized the area. They were bad women, they were out on the streets, they were dispensable, they deserved to die. If the victims had been men, nobody would have asked why they were drunk, or why they were sleeping in the streets.

Even today, whenever a serial killer or mass murderer is on the loose, the tendency is to insidiously find ways of justifying their behavior—poverty, childhood abuse or trauma and so on. But how many studies are conducted on the victims or the impact of their violent deaths on their families? They quickly become statistics, more so if they are women.

What brings this on, is Cuttputlli, the recent film on OTT, in which teenage school girls are targeted by a serial killer, who leaves their faces ruined and bodies mutilated. As it turns out (and it is no longer a spoiler since the details of the plot are on the net), an illness leaves him disfigured and repulsive to women, so he slashes their faces, and leaves puppets with similar cuts as his signature. What this conveys is that if a female had looked beyond his appearance and loved him for himself, he would not have turned into a monster. Our fairy tales like Beauty And The Beast and The Frog Prince emphasize the magical powers of a “good” woman.

There are hundreds of books and quite a few films and serials on Jack The Ripper (also Ted Bundy, The Zodiac Killer and the like), but a hunt revealed just one book of any consequence about his five unfortunate victims.The women are usually judged harshly, pitied sometimes, but hardly ever appreciated for putting up with crushing poverty and the entrenched misogyny of the Victorian era. Sadly, things are not very different today.

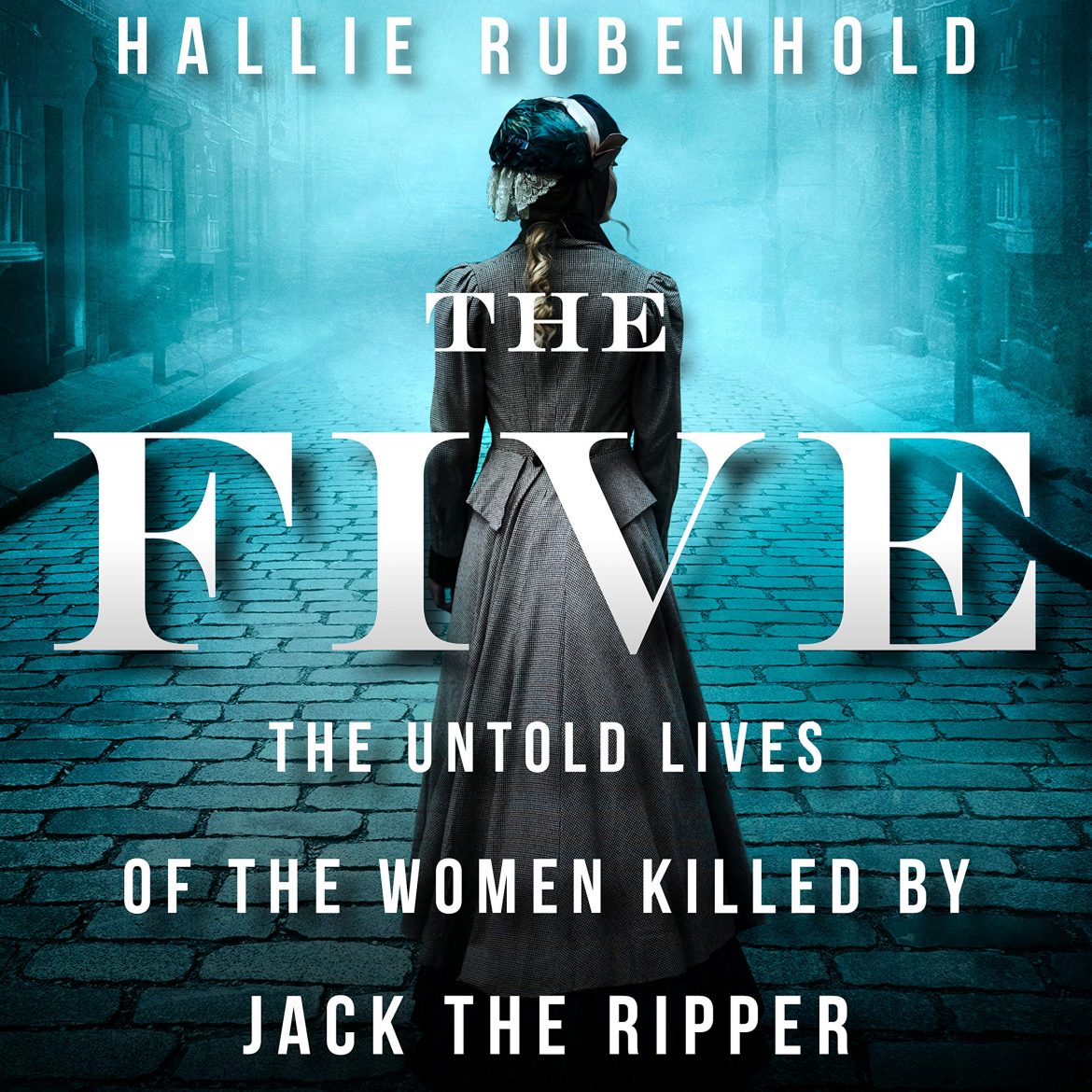

Social historian and novelist Hallie Rubenhold, in her brilliant book, The Five: The Untold Lives of the Women Killed by Jack The Ripper, has combed through numerous books, social studies, documented records, newspaper articles (an appendix lists her astounding research) to bring alive the age in which these women were born and died violently.

Because they were labelled “fallen women,” there was a callous disregard of the fact that they had families and children. Except for one, none made a living out of sex work, but ended up homeless because of poverty, abuse, desertion by their husbands. At the time, there were hardly any economic opportunities for women from impoverished families. If back-breaking and underpaid domestic work was not available, they had to resort to begging, or living in the horrible filth and squalor of workhouses. If they could not scrounge for the tiny sums needed to get a bed in a doss house for the night, they slept in the streets, and were vulnerable to sexual attacks.

What all the five women, called the “canonical victims,” had in common was poverty and large families; their mothers exhausted by repeated childbirth and endless housework, their fathers often jobless. If they could escape this cycle of hand-to-mouth existence, constantly moving from one squalid dwelling to another because they could not afford rent, it was to get married to a man, who earned enough to provide for them. But even then, they were soon ground down by hunger and want, because family planning was unheard of, or at least not practised by the working classes. Infants died of malnutrition and illness, but more children kept getting added to the family. Even boys got a bare minimum or formal education, girls were seldom literate.

The Dickensian descriptions of late 19th century life in London are shocking, as hordes of hungry, unemployed people flocked to the city. Polly Nichols, the first recorded victim of Jack The Ripper, had to walk out of a somewhat settled life in a decent home, when her husband took up with another woman. However, a woman without a man to support her, had to do whatever it took to survive.

Frances Wilson writing about the book in The Guardian states,”Forests have been felled in the interests of unmasking the murderer, but until now no one has bothered to discover the identity of his victims. The Five is thus an angry and important work of historical detection, calling time on the misogyny that has fed the Ripper myth…. The police conviction that the killer targeted women of “bad character” perverted the inquiry. The Ripper’s victims, she (the writer) suggests, were targeted not because they were soliciting sex but because they were drunk and homeless and – most importantly – asleep. The killer preyed on women whom nobody cared about and who wouldn’t be missed.”

Rubenhold writes with empathy of the heavy demands placed on the shoulders of women, the most cumbersome of all, she writes, “the ideal of moral and sexual immaculacy. As a woman was a keystone at the centre of family life, her character must be unimpeachable if it were not, it as she who was responsible for the ruin of others.”

Calling homeless woman prostitutes allowed society to look away from their misfortunes to “disparage, sexualize and dehumanize” them. “It suggests,” writes Rubenhold, “that there is an acceptable standard of, and those who deviate from it are fit to be punished. Equally,it reasserts the double standard, exonerating men from wrongs committed against such women. These attitudes may not feel as prevalent as thee were in 1988, but they persist…When a woman steps out of line and contravenes accepted norms of feminine behavior, whether on social media or on the Victorian street, there is a tacit understanding that someone must put her back in her place.”

The man who does this, becomes a legend, there is merchandize sold in his name, bars named after him, a museum dedicated to Jack The Ripper, and a walk that tourists can take in Whitechapel, supposedly following his murderous route.

Rubenhold rightly observes that by giving so much attention to Jack the Ripper (and other killers, rapists and abusers) we condone the basest of violence against women. It all very well to for social observers to humanize killers, but their victims are also entitled to respect and compassion.

(This piece first appeared in The Free Press Journal dated September 9, 2022)