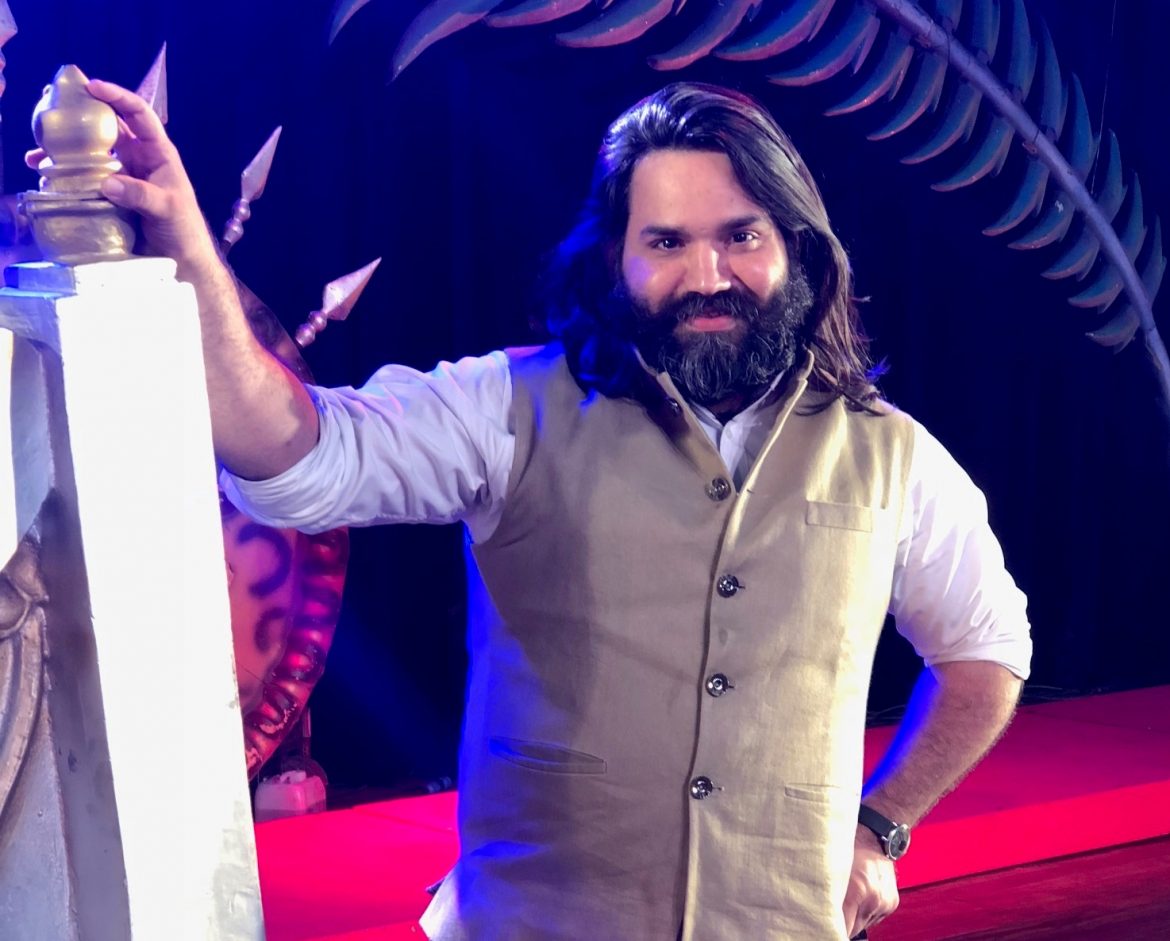

After doing theatre through school and college, when Atul Satya Koushik applied to the National School of Drama he was rejected and told he could not do theatre (due to a slight physical disability). “I thought, who are they to decide what I can or cannot do?” he says, and went on to establish his own group in Delhi, the Film And Theatre Society, which has been doing big productions, like Chakravyuha, Raavan Ki Ramayan, Draupadi, Dad’s Girlfriend, Saudagar and more recently, Ballygunge 1960 and Pajama Party, many of them with celebrities in the lead.

“In Delhi, theatre lacks the zeal and desire to be commercially viable, if not profitable,” he comments. They are happy surviving on grants or on fees charged from students. Since the yardstick of audience appreciation is not being applied, the content is not being upgraded at all. They are making plays to appease their own directorial appetites. I am not saying we should play into the hands of the audience, but there is a kind of validation if the play is liked and runs to full houses. That is the reason why, four-five years ago, we decided to commercialise theatre in Delhi.”

He studied Delhi theatre and watched every play that was staged in the capital, to figure out which direction to take. “The kind of plays that inspired me to do theatre are not what I have done so far; my theatre is very different. People may like the plays we do, but they have to come to the theatre first to appreciate them. It is not possible to do good plays with Rs 200-400 tickets. By roping in known faces like Nitish Bharadwaj, Puneet Issar, Rakesh Bedi, Himani Shivpuri, we were able to raise ticket prices, so at least the economics work. For this we are labelled outsiders in Delhi—yeh to commercial theatre karte hain. We have fought back through our work. Nobody goes to see anybody else’s plays, so there is hardly any communication between Delhi theatre people, unlike Mumbai, where people meet and discuss one another’s work. In Delhi, the environment is not conducive, there are not enough venues. At this rate, Delhi will take 20-25 years to catch up with Mumbai.”

He does not think that the NSD had done much for theatre in the capital. “The NSD is a unit that exists within four walls, that has no interaction with what is happening outside. They will take plays from anywhere for their Bharangam Festival, but won’t invite a director from Delhi. Anyway, Bharangam does not run my group, but the way they curate their content can be questioned. Because NSD does not survive on the audience’s ticket buying, they do the kind of plays they like, they have an air about them, and their interaction with non-NSD producers, directors and actors is zero. I respect NSD only because of some amazing actors it has given to this country, and hope it continues to do so.

“The irony is that the NSD-ians we admire and aspire to be like, have left theatre and migrated to movies, so you will hardly find a theatre person who is famous after remaining in theatre. If you are a qualified actor, you will expect a certain remuneration for doing your work, because that is your job; you are not an amateur who has a day job and does theatre in the evening for pleasure. Delhi producers do not have the deep pockets required to pay the remuneration that respects an actor’s art. In the last 50-60 years, we haven’t been able to create a milieu where you can aspire to become a theatre professional.”

Koushik wants to shift his base to Mumbai in the near future, for the better opportunities and talent. “Mumbai actors are more organized. They plan things in a way that leaves weekends free for theatre. Whenever I approached a star, they were kind enough to give me a hearing, and agreed to do my play because they liked the script. In Delhi, they will sit idle waiting for a big shoot. Professionalism is also lacking. I am not complaining, but these are issues we this every day.

He also resents the fact that in the North belt, a ticket-buying culture has not yet developed. “There is money in tier two cities and a hunger for good content, but that mentality of buying tickets to watch a play is not there yet; that process of evolution will take time. But I see it as a responsibility to give an audience value for money, and offer them an experience that makes them understand that theatre is a premium art. I believe the first round of applause should be for the set. That’s another reason why I want to work in Mumbai—there are so many venues, a professional working atmosphere and a ticket-buying audience. In Mumbai, nobody ever demanded a pass, in Delhi that’s a problem. I am planning to get a few of my plays translated into Gujarati, and do some plays in English so that we can travel to the South and also abroad.”

When Koushik decided to form his own company, a decade ago, he decided to do more original plays than just pick famous scripts. “I keep hearing complaints that no new playwrights are emerging, but who is giving them a break? We have a writer’s desk, people come with ideas and we work on developing them. When we do historicals, extensive research goes into them. I did a suspense thriller–Ballygunge 1990— because it is not a genre that has been explored enough. I am also keen to do a horror play. I know there will be a flood of musicals over the next few years, but we are also planning one. The talent for play writing is, I think, something connected to my past life; I do nothing special. I read a lot, I mull over an idea for a few months, cook it in my head, and write a script in four days.”

Koushik studied to get CA and law degrees, but theatre was where he wanted to be—as producer, director and playwright. “Like every parent, mine too discouraged me from taking up theatre, mainly because they wanted me to have a secure life. There was a period of struggle, but now that they see that I have some money coming in, an office, a staff of 12 and a team of 60 people, they are happy. However, very soon theatre will have to prove that it is a profession to aspire to; that is it not a route to films, but a goal in itself.

“My education was not wasted. I know how my knowledge of finance and law helped me to build a theatre company from nowhere, with no background. Also, when I go to meet corporates, it is not to beg, but to make presentations on how our content will help their social brand image building how to do brand integration in my plays. They like that we speak their language. Apart from that, we do workshops with corporates on management and goal achievement through theatre. So I have combined my education with my interest in theatre. The lack of a formal theatre education may have closed some doors for me, but had I got into NSD, I would have been trying to direct a film or running after a TV serial.”

(This is a slightly modified version of the piece that first appeared in The Hindu Friday Review on October 12, 2018)