As the new Sara Paretsky novel, Dead Land, is released (and immediately picked up), it leads to musings about the female detective in fiction.

Paretsky created the wonderful character, V.I. Warshawski, in 1982, with the book Indemnity Only, and went on to write twenty books with the female private investigator as the protagonist. A few months later, Sue Grafton started her alphabet series of crime novels, with A is for Alibi with the gutsy Kinsey Millhone as a detective, and went right up to the letter ‘Y’, sadly passing away before she could complete ‘Z’.

These two women have a lot in common—they are both single, unwaveringly honest, socially aware, compassionate, lean, athletic and fearless. They heralded a new era of crime fiction with female private detectives who were professional—that is, they made a living out of this work. They were not amateurs like Nancy Drew (multiple authors), the teen detective all young readers grew up on, or Agatha Christie’s elderly busybody sleuth, Miss Marple—both hugely popular characters made their appearance in the 1920s.

Warshawski and Millhone have complicated family histories and backgrounds in law enforcement, before they got disillusioned and set up their own one-woman businesses.

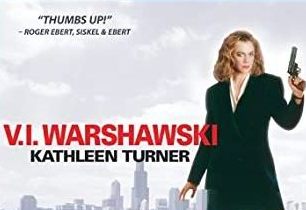

Victoria Iphigenia Warshawski, called “Vic” by her friends (she hates Vicki), is the daughter of Italian-born Gabriella Sestrieri opera singer, a refugee from the Mussolini regime, and Anton “Tony” Warshawski, a Polish-American police officer in Chicago. She lost her parents by the times she was in her early twenties, and grew up having wild adventures with her cousin Boom Boom (whose goddaughter Bernie appears in Dead Land) and became adept at street fighting. Getting into the University of Chicago on a sports scholarship—she played basketball in school—she became aware of, and involved in, political issues of the time, taking part in rallies against racism and demonstrations against the Vietnam War. She got a law degree and worked as a public defender for a while, before getting disenchanted with the American legal system and becoming a private detective. She had a brief marriage with a fellow law student, and remained unmarried—though not single—after her divorce; in the latest book, she is dating an archaeologist. In spite of her constant exposure to violent crime, she has not become cynical and goes out of the way to take on powerful and wealthy wrongdoers, including evil corporate honchos and corrupt politicians. (Kathleen Turner played her in the 1991 movie, sadly the only one starring Vic.)

Sue Grafton’s Kinsey Millhone is the daughter of a rich girl Rita, whose family disowned her after she married postal worker, Randy Millhone. Her parents were killed in a car crash when she was five, and she was raised by her mother’s sister, Virginia or Aunt Gin, who, according to Grafton’s backstory for Kinsey, “was also estranged from the family and living alone in Santa Teresa. Ill-equipped to inherit a daughter, she did her best to raise Kinsey. She was a no-nonsense kind of person who instilled in Kinsey a strong sense of independence and self-sufficiency, both of which would serve Kinsey well throughout her life. Other traits received or reinforced by Aunt Gin were an aversion to cooking, a lack of interest in fashion, and an affinity for books.”

Aunt Gin died when Kinsey was in her early twenties, and the kid grew up into a rebellious student, but after graduation, joined the Santa Teresa Police Department. “She had trouble dealing with the bureaucracy and the attitude toward women officers at the time and she quit after two years. Kinsey had two brief marriages. Almost nothing is known about the first except that Kinsey left him. The second husband left Kinsey unexpectedly, but shows up years later in one of the novels. In her mid twenties, Kinsey studied to become a private investigator, got her license, and landed her first job with a detective agency a couple of years later.”

Eventually, Kinsey went freelance, got her own office and finally moved out of trailers and into a studio apartment. She lives there with a kindly octogenarian, landlord, Henry, and frequents Rosie’s tavern nearby.

Both characters have had unusual lives that make them what they are—fiercely independent. However, they are not loners; they may be reluctant to make long term commitment, but have relationships with suitable (at the time) men. There is no gender ambiguity about them—their favoured outfits are jeans, T-shirts and running shoes, but they clean up nice. Vic can cook and has a decent wardrobe; Kinsey makes do with junk food and has one all-purpose wrinkle resistant black dress.

There were female detectives before Warshawski and Millhone, but they were, in the works of author Dorothy L Sayers, boxed into a stereotype of being “young, beautiful, inclined towards domesticity, and too often prone to walk into physically dangerous situations and interfere with men trying to solve crimes.”

According to deadgoodbooks.co.uk, “A great deal of debate has developed about the exact moment the first fictional female sleuth made her debut. But it’s generally agreed that The Female Detective, published in 1864 (or possibly in 1861) by Andrew Forrester (the pen-name of James Redding Ware) was the first work in this new genre. His character, Mrs Gladden, investigates crimes in a professional capacity, and is paid for her services. Another author, W.S. Hayward, was in close pursuit with Revelations of a Lady Detective, featuring another heroine who earns a living as a private eye.”

Interestingly, women were not formally recruited into the police force in the UK till 1924, so if there were to fight crime, it had to be as a private detective, or a sidekick to a male investigator. Otherwise, they appeared in thrillers as vamps or murder victims. Besides, it would be difficult to chase criminals while dressed in voluminous skirts, though Mrs Paschal in Revelations of a Lady Detective, did take off her crinoline to go down a sewer, and also showed “the sort of clinical reasoning that Sherlock Holmes would display decades later.”

In her essay Desires and Devices: On Women Detectives in Fiction, Birgitta Berglund writes, “In novels written by men, women detectives are very few indeed (although they do exist) but even in books written by women, male detectives dominate. Thus we have, for instance, such notable fictional detectives as Hercule Poirot, Lord Peter Wimsey, Albert Campion, Roderick Alleyn, Adam Dalgliesh and Reginald Wexford – all of them created by women. In Sisters in Crime: Feminism and the Crime Novel, Maureen Reddy suggests several reasons for this situation. One is that writers who want to reach large groups of readers tend to choose a male protagonist rather than a female one, as women are on the whole much more willing to read about men than the other way round: girls read the Hardy Boys series but few boys would want to be caught with a copy of a Nancy Drew book in their hands.”

The first real-life female detective is believed to be Kate Warne, who started working in 1856, with the agency set up by Allan Pinkerton in 1850, and may have been an inspiration for writers of crime fiction.

Now, there are several thrillers with female cops, private detectives, a maverick crime fighter like Stieg Larsson’s Lisbeth Salander, or a wise problem solver like Alexander McCall Smith’s Precious Ramotswe, but it took many years and much jumping over obstacles to reach this point. V.I. Warshawski and Kinsey Millhone may have given many of them a big helping hand.

(This piece first appeared in The Free Press Journal dated May 6, 2020)